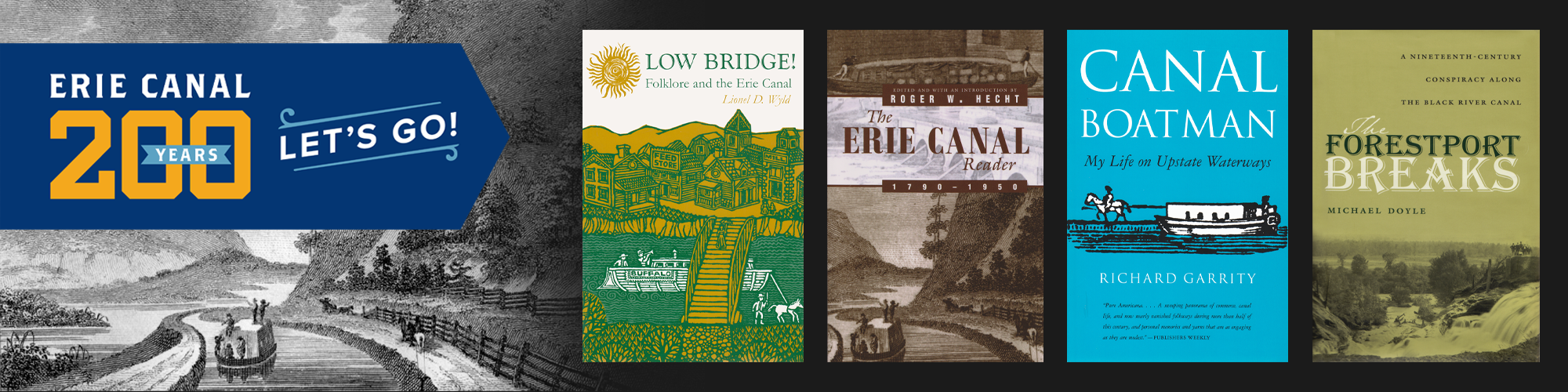

For canallers, life and work while working on the Erie Canal could be a monotonous, occasionally deeply dull affair, especially when stuck in a port, living cheaply, and usually far away from home. In Low Bridge! Folklore and the Erie Canal by Lionel D. Wyld, old accounts of canallers’ many, often less than savory, methods of passing the time are described. Wyld’s book includes many passages directly from journals, letters, and newspapers at the time, and the typographical errors are reproduced here as originally printed.

The average canaller seems to have been a combination of perennial adolescence and hearty, frontier-type masculinity. Like any major artery of traffic, the Erie Canal was by nature democratic, and the canallers’ amusements, like their language and customs, were those of American pioneers living in the open and thrown upon their own resources. During its heyday the Erie Canal was anything but the “dull utility” it became later as it was forced in to the pattern of a progressively urbanizing New York State. Towpath and berm teemed with activty, diversional as well asessential. As an erstwhile canaller put it, “What a moving marvel of humanity was the old towpath.”

The record shows that canallers would fight at the drop of a hat but it also shows them to have been friendly and convivial. They were, of course, without societyish restraints and refinements, but their brawling, although frequent, seldom had real malice in it. While some of their sports involving animals would be regarded as cruel today, it was not until the second half of the nineteenth century that reforms of the treatment of animals were undertaken in America. On the basis of some of the material following in this chapter, the term “fun-loving” applied to canallers may see euphemistic, but less so if they are judged by the standards of their times.

Canalside sports and contests were doubtless not unique to Erie water, but representatives of activities found along other regions. Races between cockroaches, grasshoppers, bedbugs, and frogs were common. Walter D. Edmonds tells a delightful tale about caterpillar-racing, apparently a sport which developed no small following along the Erie. The story is told by a canal-family lad and there were rules and protocol to be observed. “The way we raced caterpillars,” her said, ” was to set them in a napkin ring on a table, one facing one way, one the other. Outside the napkin ring was drawed a circle in chalk three feet across. Then a man lifted the ring and the handlers were allowed one jab with a darning needle to get the caterpillars started. The one that got outside the chalk circle the first was the one that won the race.” “Red Peril,” the real hero of the tale, and “The fastest caterpillar in seven counties” proved to be a real champion. His trainer, a known “connesewer” in caterpillar-racing, found Red Peril scared of but one thing— butter, a trauma effected by having once been immobilized in it. His last race was against the “Horned Demon of Rome,” a race he won valiantly, by expiring on the chalk line.

Cockfights were popular with canal men. One chief gathering placed seems to have been Leonard’s saloon on the “Dyke” or lower Cohoes, where canallers frequently paid off their debts in fuel, keeping the enterprising saloonkeeper in winter supply. The sport of cockfighting finally became illegal in New York State, and by 1880 newspapers carried accounts of raids on the cockfight “arenas.” Bulldog fighting used to be another sport which an S.P.C.A. would not have tolerated. The haunches of the dogs were sandpapered until they were raw in order to get the dogs fighting mad and cause them to tear into each other.

Betting, whether on cockfights or other game contests, was part of the canaller’s diet. They literally “bet on anything.” Schoharie Crossing, where the canal passed over Schoharie Creek, often proved to be a particular source of dismay in rainy weather. Since it was a highly dangerous undertaking, few canallers, including the most experienced, would venture to cross the feeder until the weather cleared and the waters abated. Any fool who tried to tempt fate by failing to wait it out would immediately draw heavy betting from the onlookers regarding his chances.

A canaller who stopped by the McClare Hotel in Rexford be the bartender a dollar he could down a gallon of hard cider without taking more than three breaths. When the bartender took him up on it, the canaller excused himself for several minutes, the returned, gave the jug a full tilt and emptied the contents. The bug-eyed bartender handed over a dollar, shakings his head that he had not thought it could be done. “T’ tell the truth, neither did I,” said the “till I ran down to the neighbor tavern to find out!”

Gambling and liquor, needless to say, provided another constant diversion for canaller of all sorts. “one captain writing to his relatives in 1882 confessed that he had “sined the pledge” and “don’t shak any dice or play any more gambling games.” The man found ample reasons for the wisdom of his changed ways. In his letter he commented, “There was a Capt of a boat Drowned a little while ago by the name of mike Heart left a Wife and six Children Caused by being drunk and falling in between to Boats.”

“I have seen enough of that kind of business so that I am satisfied to leave all intoxicating liquers alone,” he concluded.

This was written during a winter layover, when the Hudson River ice was eight inches thick. Three years earlier, in Rome on the Erie, a combination of freezing weather and snow closed the canal. Under date of “november 21, 1879” the canaller wrote: “. . . Well we lay about one mile and a quarter from Rome West there is about fifty or 100 boats between here and the feeder it is all Blocked in with snow and ice So the boats cannot move the ice breaker has not worked at it yet. . . . I think it will be doubtfull weather we get through rome or not his fall it is fearful Coald weather I froze my rite ear last night and it is freezing hard to night Pa says it acts just as it did that fall we froze in here. . . .”

Two situations – this being “froze in” and encountering washouts or breaks — often caught canallers in ports not of their own choosing and made them turn to the communities for diversions (or to think up their own) to while away the time, in the one case usually until the spring thaw, and in the other until a repair crew again opened the canal to traffic. Sometimes the inititaive of the canallers manifested itself commendably. An upstate newspaper report upon two major breaks ran the following account.

The Raging Erie Canal

A Washout on the Black River and a Cracked Wall at Frankfort give Cooks Time to Have Pink Teas and Crews Leisure to Form Literary and Political Clubs

The break in the canal early last Sunday morning gave a few hundred canal men a rest they didn’t want, and cost them a lot of money they couldn’t afford to lose.

The lay-up came in the way of a bonanza of restfulness to horses and crews, but it was as welcome as sulfuric torments to the owners who saw drivers and steersmen with healthy appetites for corned beef and cabbage and horses eating their heads off in solemn ease with their noses buried in hay or oats.

It costs from $10 to $15 a day to run an ordinary horse-boat and, while canal captains are a philosophical lot, it takes more than a commonly philosophical mind to see the bottom dropping out of his pocketbook and his money floating off as fast proportionately as the muddy water rushing through the sewer and off to the ocean.

It was all right for the cooks who could go visiting other cooks, getting up pink teas and five o’clocks for their friends. And it wasn’t bad for the drivers and deck hands who could form literary and socials, organize silver clubs and meet for the discussion of theological problems, but the poor owner had to pay the piper for the dancing and he looked as sour as if he had been condemned to a diet of green persimmons and young apples and expected to endure aches and pains eternal.

The press commented on the fact that, due to the economy-minded canallers, stores in town did not make money by the disaster. Even the “liquor repositories” near by, continued the reporter, got little additional profits “for the navigator, when he is navigating, doesn’t carry cash, and his bibulous tendencies are laid aside for indulgence in one wild bath of been when the season is over.”

Both canallers and townsfolk came in for commendation under the circumstances.

It might have been thought that potato patches and henneries would have suffered under the visitation of a couple of thousands canallers but they didn’t, and they impressed the community with the fact that they are as superior to temptation as anything human between the great fresh lakes and the blue salt sea.

Perhaps the most astonishing feature in connection with this involuntary assembling of two great fleets is that it was not taken advantage of by any of those who might have seized the opportunity. No missionaries from the Volunteers or the Salvation Army went on a peregrination to save sinners; no peddlers with things to sell which no rational being would be without visited them; no insurance men went up there or down the other way to write policies on life or underwrite the boatmen for compensation in case of accident. Like a lot of Sir John Mores they were left alone in their glory, and the chances are they’re glad of it.