Behind every great fortune there is a crime, and behind every noble proclamation there is politics.

Granted, as aphorisms go, mine may not sing quite like Balzac’s. But as we celebrate University Press Week and raise up those books that some would ban or burn, let’s remember this: Proclamations don’t just happen. They must be worked at to matter.

Take the urtext of University Press Week, the proclamation signed on June 14, 1978 by then-President Jimmy Carter recognizing “American University Press Day.”

Funny thing was, Carter signed the proclamation three days after the designated day of June 11 had passed. This after-the-fact timing, akin to bidding the world Happy New Year on Jan. 4, wasn’t Carter’s fault. It was Congress’s doing, with its resolution that “authorized and requested” the president to issue said proclamation.

Congress, being Congress, dilly-dallied and then rushed Senate Joint Resolution 140 in a manner that could have caused problems when the House of Representatives took up the measure on June 9, 1978. The day’s Congressional Record transcribed the action.

“I just hope in the future when the gentleman has something like this to bring up, he will do it ahead of time,” said Rep. John Rousselot, a Southern California Republican and John Birch Society member who put the arch in arch-conservative.

“I will be glad to do that,” Rep. Clarence Long, a Maryland Democrat, replied, adding plaintively that he was “only asked to do it a few moments ago.”

Indeed, the Senate had passed the resolution less than 24 hours before. All of this last-minute scrambling rendered the measure vulnerable to procedural resistance by the John Rousselots of the world.

Lesson One: Proponents of even the most virtuous cause must get their act together or risk technical default.

Still, despite their inapt timing, the resolution’s authors did pass the political science problem set. They understood congressional procedure. They secured floor time from party leaders. They mollified potential antagonists who might otherwise interrupt the work. Not least, they answered to their constituents. The two Senate backers of S.J. Res 140, Democrats Paul Sarbanes and Charles Mathias, were, like Congressman Long, from Maryland. That’s Maryland, home to The Johns Hopkins University, the very institution celebrated for having established the first U.S university press in 1878.

Lesson Two: Heed former House Speaker Tip O’Neill’s adage that all politics is local.

And, who knows, perhaps there’s even more to this story buried somewhere within the 973 cubic feet of Mathias’s official papers held in the Johns Hopkins archives. If there are S.J. Res 140 secrets to behold, no doubt it will be a resolute university press author who finds them.

Why do I say this? Check out this year’s #StepUP reading list, each title a proclamation of both vision and persistence. There are books about story quilters, African-American midwives, neurodivergent scholars, a World War II infantry division commander and more. Each one suggests both an author’s unique passion and a publisher that can picture a pearl where others see but a grain of sand.

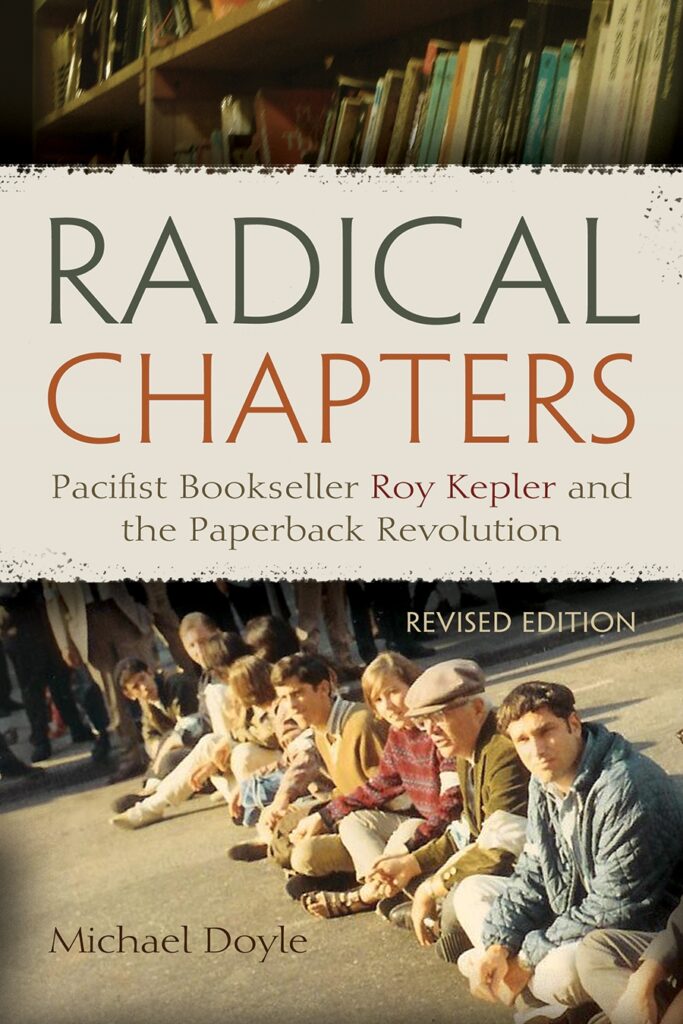

That certainly was the case with my Radical Chapters: Pacifist Bookseller Roy Kepler and the Paperback Revolution, many years in the making and published in 2012 by Syracuse University Press. As it happens, its reappearance this fall in paperback coincides with a resurgence of some challenges akin to what Kepler’s Books & Magazines faced when it opened in Menlo Park, California in 1955.

You say today’s book banners threaten free speech? The 1950s and ‘60s say, hold my beer.

In January 1957, just as Kepler’s was getting started in the paperback business, Detroit’s police censor banned sale of the 50-cent paperback edition of John O’Hara’s novel Ten North Frederick. The censor feared the low price might lure minors into sin. The city’s deliciously named Police Commissioner Edward S. Piggins extended the ban to include hardcover editions.

“This is not a book I would want my sons to read,” Piggins explained.

It took a lawsuit from Random House and Bantam Books to get the ban lifted two months later. Put another way, the publishers backed up their denunciations of censorship with competent legal action and its accompanying billable hours.

It was in much the same censorious climate that the Menlo Park chief of police personally directed a Kepler’s clerk in the store’s early years to remove Playboy from public display. The clerk complied. When Kepler learned what happened, he promptly restored the titillating magazine to the public shelves.

“My store is not operated on the basis of allowing the police to select which books or periodicals shall appear,” Kepler said.

Still later, in the feverish late 1960s, Kepler’s front window showcased books about China and an iconic poster of Mao Tse Tung. On the morning of Oct. 16, 1969, workers discovered a broken front window, a hatchet and an ominous note.

“First Chairman Mao,” the note warned. “Then Kepler.”

The peculiar case was finally cracked by the same Menlo Park Police Department whose chief had earlier tried to yank Playboy off of Kepler’s shelves.

Kepler’s Books and Magazines is still going strong; but so, too, are the forces of speech restriction. Only now, it’s not just a single police commissioner shielding teenagers from the likes of John O’Hara. School boards and state legislators are getting into the act. During the first half of the 2022-2023 school year, PEN America recorded 1,477 instances of individual books being pulled out of public schools and libraries, an increase of 28 percent compared to the prior six months.

John Rousselot, the right-wing congressman who lamented the lickety-split consideration of the “American University Press Day” resolution, passed away in 2003. But as the PEN America numbers suggest, hardline sentiments live on. University Press Week of 2024 is a time to remember the hard work that our own worthy sentiments may demand.

Michael Doyle is a reporter in Washington, D.C. with E&E News/POLITICO and the author of three books published by Syracuse University Press.