Richard Garrity spent much of his youth on the Erie Canal, with plenty of happy memories both along the waterways and on tugs and boats along the river. Garrity would go on to work as a boatmen as a young man, recording his memories years later in Canal Boatman: My Life on Upstate Waterways. In the below excerpt, Garrity remembers his first journey along the newly opened, expanded Barge Canal, which offered a new peak at familiar waters for the experienced boatman.

When the Barge Canal opened on May 15, 1918, I had hired out as a fireman on the tub Liberty, a large steam tug which was chartered to the government to tow on the new canal. The wagers were based on a monthly scale for a twelve-hour work day and included board. The Captain received $175 per month, Mate $150, First Engineer $150, and Second Engineer $120. The two firemen and the cook each received $90 per month. The tug operated night and day, and all the crew , except the cook, worked six hours on duty and six hours off.

The employer allowed 90 cents per day, per man, to feed the crew. The Captain received a subsistence check each month and handled what was called the “grub money.” It was always suspected that he and the cook split up any surplus money that might be left at the end of the month. Nonetheless, I was usually satisfied with the amount and quality of the food, although there were always some growlers amongst the crew. The growlers were the cause of some of the grub money handlers’ acquiring the name of “belly-robber,” along with some harsher epithets.

On the tub Liberty, the Captain and Mate slept in the after part of the pilot house, in a small, fairly comfortable room containing two bunks. The rest of the seven-man crew slept below decks in the forward end of the tug. The forespeak contained four lower and four upper bunks. It was a fairly comfortable place to sleep in the spring and fall, but it was like an oven in July and August. Sanitary facilities consisted of only a water closet. Washing up was done in canal water dipped up in a deck pail or hot water drawn from the boiler water supply; a bath was had by the same method. Hot water was plentiful on a steam tug and was also used by most of the crew for hand laundering their own work clothes.

While going through the canal, life took on a monotonous routine. At the end of your six-hour shift, you washed up, ate your meal, sat around for a while, and then went to bed. You were called a half-hour or so before the start of your watch, ate your meal, and then started another six-hour shift. Passing through a town was a welcome break in the mostly rural scenery. Passing through a lock was an interruption of the monotony and provided a half-hour or so of relaxation for the crew and short rest for the fireman.

For single or footloose men, the life on a canal tug provided just about everything needed except recreation. There were some who found this in a barroom at each end of the canal. For the others, it was work they knew and liked, and it provided the wages needed to support their families. As for me, I enjoyed the work and was contented to work on the canal until I was married in 1928. After that, canal life lost its appeal because of the time that had to be spent away from home and family during the navigation season.

When I hired out as part of the crew, the tug had recently been converted for canal towing, and we stayed in Tonawanda a few days waiting for orders from the canal dispatcher. We used the time to check out things in general and to take aboard needed equipment and other supplies for our first trip over the new canal. There were not canal fleets to tow east, as very few boats had wintered in Buffalo. We finally received orders to proceed to Waterford with the light tug. We ran night and day as far as Lyons, except for the fourteen miles of new canal passing to the south of Rochester. The Barge Canal just about followed the route of the old Erie Canal to the beginning of the canalized Clyde River at Lyons. From here on, we tied up when it became dark, as neither of the pilots was familiar with the canalized rivers used by the new canal, most of the rest of the way to Waterford. In spite of being urged by canal supervisors and dispatchers, there were few if any rowboats operated after dark upon the canalized river sections of the new canal, until the pilots made a few trips over the route and became acquainted with the channels . . . .

On this first trip in 1918, we passed Brewerton on a nice spring day and the run across Oneida Lake was made in a little over two hours with the light tug. We left Sylvan Beach behind and then passed through Locks 22 and 21. They are the same locks for which we unloaded gravel at the hamlet of Grove Springs. The hamelt is no longer there, having been absorbed by Stacey Basin after the closing of the Erie Canal. The run from here was over an artificial or man-made canal to Frankfort, where we entered the canalized Mohawk River.

The next point of interest was the lock at Little Falls. This lock replaced four Erie Canal locks and has a 40.5-foot drop, and a lift gate at its lower end instead of swinging gates. The eight bridge dams at the locks along the Mohawk were something new and interesting to the crew as they were the first dams of this new type that we had ever seen. At this time, an old wooden suspension bridge spanned the Mohawk River at the foot of Lock 12 from Tribes Hill to Fort Hunter.

At Schenectady, some of the spans and piers of a very old and odd-looking covered wooden bridge were still to be seen in the Mohawk, the center part of the bridge and piers having been removed for Barge Canal navigation. A little farther along the Mohawk, at Rexford Flats, we passed between the remaining piers of the old 610-foot-long Erie Canal upper aqueduct. After leaving Rexford, the river kept widening out, and we next passed through Lock 7 at Visher’s Ferry with its 27-foot-high, very wide fixed damn. Then 12.7 miles from the upper aqueduct we went between the remaining piers of the longest aqueduct on the old Erie. This 1,137 foot span crossed the Mohawk at the village of Crescent.

A mile or so farther on, we entered a land cut that contained two guard gates and five new locks which are sometimes referred to as the Waterford Flight. This flight replaced the 16 Erie Canal locks on the south side of the Mohawk at Cohoes. The greatest distance between the locks is about 0.6 miles between Locks 3 and 4. The other locks are spaced about a quarter-mile apart. When descending the Waterford Flight from the Mohawk to the Hudson Valley, boaters had a view that reminds one of a great set of stairs.

My first trip with the light tug Liberty over the new canal had been uneventful but it was nevertheless very interesting. We had arrived at Waterford four days after leaving Tonawanda; had we not tied up at dark, we would have made it in three.

We laid idle in Waterford seven or eight days waiting for our tow of boats to arrive from New York City in a Hudson River tow. While waiting, all of the crew were getting a full night’s sleep, and we were quite content to be fed and paid for loafing. As firemen, my partner or I banked the fire at night, and if the engineers so ordered, we let the steam rise in the boiler in the daytime.

I recollect that my partner’s and my loafing was interrupted by having to replenish the tug’s drinking and cooking water supply. There being no freshwater tap or outlet on the terminal, we had to do it with pails by walking with one in each hand to a water tap half a block from the tug. We must have made fifteen trips each to fill the water storage container aboard that tug! I ought to have mentioned it before, but large tugs from the Buffalo area carried no deckhands, and although I was hired as a fireman, I had to handle towlines and tie-up lines and take care of other duties that were usually handled by a deckhand. Later on the larger Barge Canal tugs carried two deckhands as well as the two firemen.

Under the firemen-deckhand arrangement, were were at the beck and call of the Captain, the Mate and the engineers. So, to keep us from getting too soft and lazy while waiting for our tow, they had us scrub the inside of the pilot house and engine room. This we did, while the Powers that Be did the heavy thinking.

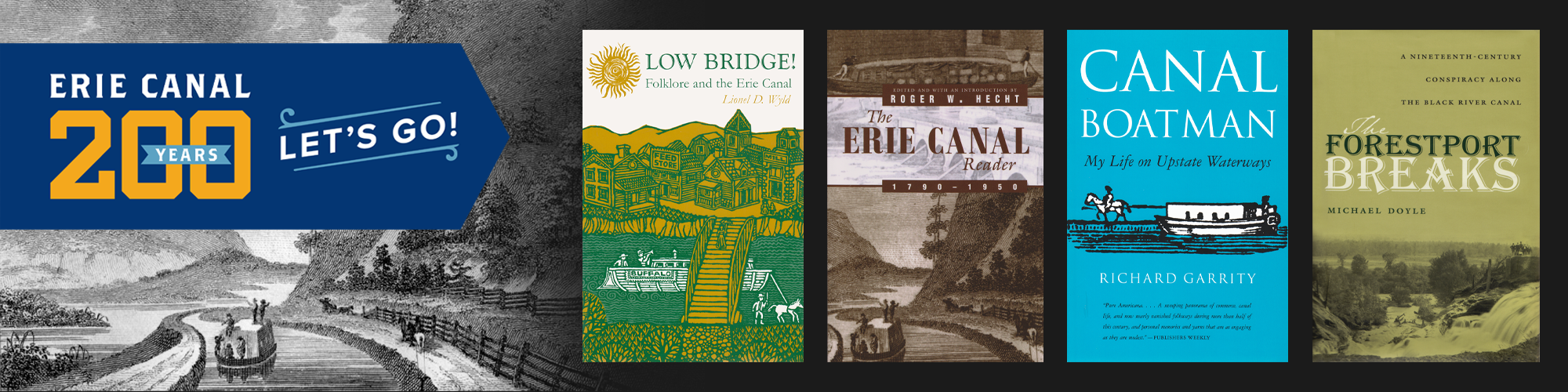

Order a copy of Canal Boatman here.