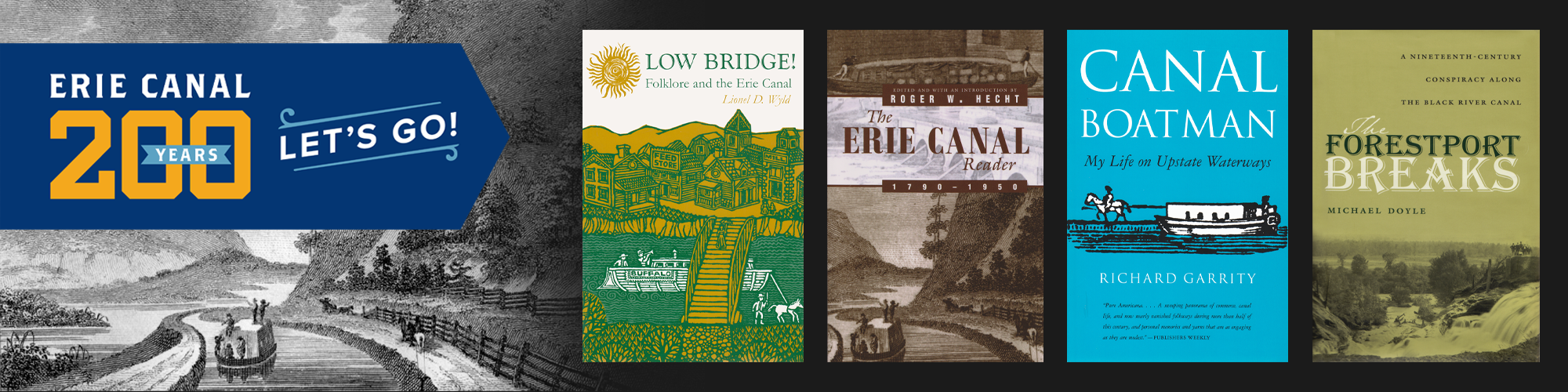

The Erie Canal developed its own unique folklore and tall tales, often shared by the canallers who worked the waterways and the people who lived alongside them. In Low Bridge! Folklore and the Erie Canal, author Lionel D. Wyld recounts some of the tall tales and legends that sprung up around canal life. Wyld’s book includes many passages directly from journals, letters, and newspapers at the time, and the typographical errors are reproduced here as originally printed.

Canallers’ tales stemmed from actual canalside incidents and the persons involved in the. Not infrequently, of course, the stories became exaggerated or a storyteller got hold of a real yarn and thus would begin the fabrication of a “Whopper,” growing into a full-fledged tall tale recognizable in variants by folklorists the world over. Sometimes the literary craftsman plays a part too, adapting for his purposes folk material which subsequently is remembered more in the literary version than in the original of folk tradition.

One enterprising “captain,” for example made history of a highly interesting sort in the 1880’s, when he conceived the idea of exhibiting a whale on the Erie Canal. A native of Sag Harbor, Oakes Anderson went into partnership with three other Long Islanders, took a whale captured off Cape Cod and had a Boston professor go to work on it with barrels of embalming fluid. Mounting the 65-foot fin-back on a barge, Oakes added a tent, hired a professional lecturer, and set off on a tour of the canal and other waterways with a $6,000 investment.

He toured across York State, over into Ohio and up and down the Mississippi, piling up cash from curious patrons en route. Health departments and other critics found that in comparison to Anderson’s whale, the smell from Barren Island (where New York City once dumped its garbage) was like sweet attar of roses. Eventually, his partners left him, he discharged his paid hawker, and Oakes Anderson had a slightly used whale on his hands. he couldn’t sell it or give it away, and one time his barge sank in the canal, whale and all. The smell finally went away, as the whale dried to mummified condition; but what finally happened to the whale no one knows. Here, at any rate, was a canaller about whom it was said his Yankee wit and power of exaggeration made him second only to P. T. Barnum as a showman

The story, sometimes modified by the years, reached Walter D. Edmonds. “Someone told me,” he said, “That a canaller had stabbed a whale in the eye on his way across the Harbor and exhibited it up the Hudson and the canal . . .” Edmonds went to work on the story and produced “The Cruise of the Cashalot” for The Forum and Century in 1932; his canawler managed also to get rid of the whale: he sold it for fertilizer for eighty cents. A 65-foot whale on the Erie Canal thus became one kind of Erie tale.

But Erie Canal stories —whether authentic, apocryphal, or invented— throw light on the nature of the canaller and of “Canal culture.” They keep alive, half a century after its closing, something of the spirit of what Samuel Hopkins Adams called “that vast Clintonian enterprise.”

The Erie tall tale in many cases is a recognizable folk tale type transplanted as it were, to Erie water. A variation of the culture hero motif, St. Patrick’s version, for example, concerns snakes in and along the Erie Canal, the bane of towpath life. A packet skipper named Joe seems to have been responsible for ridding the Erie towpath of them, helped by the indomitable descendants of Erin. Going through a school of water snakes once, the canaller’s boat lost an Irish greenhorn who fell overboard. According to the story, the Irishman hadn’t washed since he left Ireland and the snakes in the canal died of poisoning right then and there. This gave Joe an idea. Since most Irishmen, carried a bowl filled with Irish field dirt, Joe took a handful of the dirt from each of the Irish passengers aboard, and scattered it liberally on the banks along the canal as he went along. Since that day, few snakes have come near the towpath.

The towpath mule, being the most cussed animal in Yorker country, naturally evoked much tall-tale attention. One canal tale involves a boatsman who tried to raise bees on his canal boat, but when the hives swarmed near Pittsford, locktenders armed with whippletrees caused a near riot. Once the mules strained so hard to get away from the bees that they stretched a brand new towrope, an inch and a half thick, so much it could be used for grocery twine.

Agnes was different. A Civil War veteran turned to towpath work, she pulled barges for ten years or so, until her captain sold her for ten dollars to a young Virginian visiting Albany. The Agnes really began to come alive. The Virginian took her to his Richmond plantation to plow peanut fields, but Agnes had other other ideas. She took a liking for red coats and fox hunts , and bounded after the hounds. As a matter of fact, she put her ears up, passed the hunters, jumped fences like a kangaroo, and got to the foxes before the hounds. After that, there was no holding Agnes once she heard the dogs on the track of a fox.

Then there is the story of the giant squash. One year a big drought hit the Erie, and the canal and its feeders were almost dry. A woman in Weedsport was arrested for filling her washtub from the Erie and thus stranding fifteen canal boats. towpath walkers all that summer went along the canal cutting weeds and vines so their roots couldn’t suck any water from the canal; they carried shotguns to fire at the crows and sparrows that tried to drink. One fellow from Eagle Harbor way made out all right, though. He had a squash vine that he had been nursing along by spitting on it every so often. When he finally stuck the roots into the canal to water them, the vine dragged out water like a big hose and left ten miles of the canal bottom bare. The plant swelled so fast the farmer had to run to keep from getting squashed. The plants swelled like rubber balloons, and one section of the vine actually passed him, going like a racer snake; he grabbed at a flower-bud, but by that time it had turned int o a flower and then into a good-sized squash so fast it blew off his hand as a fistful of gunpowder would. He made a living for years selling sections of the vine’s leaves—the veins made good drainage tile.

The story has appeared in other versions as the Palmyra squash, with slight variations in the telling.

Over Rome way, another story, reminiscent of Paul Bunyan legendary, concerns a giant frog. In the early 1850’s a young lad named Red McCarthy took a polliwog from the Erie Canal along Rome’s South James Street. This was the canal-spawned origin of Joshua, the famous from of Empeyville—a 100-year-old giant, with hind legs six feet along and ana appetite that was said to have devoured chipmunks, squirrels, and sometimes rabbits. For a time after his polliwog days Joshua was missing, but he turned up several years later in the town of Empeyville. There every time he jumped the water sprayed thirty feet in the air, and the pond got six feet wider!

Yarns have sprung up around the giant frog. As an assistant sawman in Empeyville, Joshua hauled material that was too heavy for horses. He gained a fair reputation as a road-straightener too, by hooking up a chain to the roads and pulling hard. In this way he helped straighten the Snake Hill curves. As late as the summer of 1934 the Rome Sentinel reported an incident involving Joshua, four of whose grandsons, owned by man in Rome, were employed by the city as stump-pullers. Other descendants still inhabit Empeyville pond.