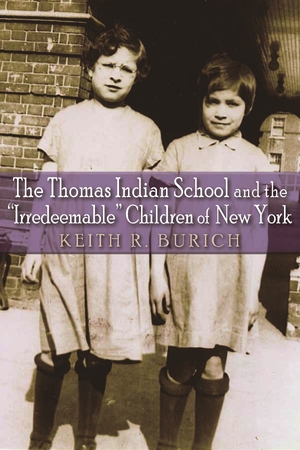

"Burich’s book fills a glaring gap in the fields of Indian education and Haudenosaunee history. It is accessible for undergraduate students and will add significantly to classroom explorations of Indian education by including state-mandated education in discussions that usually revolve around the Carlisle Industrial School and the federal system."—Holly Rine, associate professor of history, Le Moyne College

"Burich’s exhaustive history significantly contributes to the history of settler colonial schooling by documenting a distinctively different kind of Indian School: non-federal, state run, horrifically committed to the idea of the “irredeemable” Indian child."—K. Tsianina Lomawaima, professor of Indigenous education, Arizona State University

"Burich's research brings to light an important dimension of American and Native American history, reminding us that, as bad as boarding schools and orphanages were, they attempted to address real and awful conditions among Native peoples (conditions, admittedly, created by the settler state). . . . A valuable and accessible investigation that could and should be read by academics, students, and the general public."—David Eller, Anthropology Review Database

"Burich helps enlighten us on the experiences of the children who attended the Thomas Indian School. Included in his book are anecdotes from the children or inmates as they were referred to as, explaining at a personal level the many challenges they were facing."—Brian Rice, author of The Rotinonshonni A Traditional Iroquoian History through the Eyes of Teharonhia:wako and Sawiskera

"Written by an historian who knows the craft of telling a good story, Burich’s book offers a new interpretative angle to the growing literature on Indian boarding school studies, and makes a wonderful contribution to the history of American Indian education."—Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, associate professor of history, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

"Burich’s exhaustive history significantly contributes to the history of settler colonial schooling by documenting a distinctively different kind of Indian School: non-federal, state run, horrifically committed to the idea of the “irredeemable” Indian child."—K. Tsianina Lomawaima, professor of Indigenous education, School of Social Transformation, Arizona State University

"Burich helps enlighten us on the experiences of the children who attended the Thomas Indian School. Included in his book are anecdotes from the children or inmates as they were referred to as, explaining at a personal level the many challenges they were facing."—Brian Rice, University of Winnipeg, Iroquoia

Description

The story of the Thomas Indian School is the story of the Iroquois people and the suffering and despair of the children who found themselves trapped in an institution from which there was little chance for escape. Although the school began as a refuge for children, it also served as a mechanism for “civilizing” and converting native children to Christianity. As the school’s population swelled an financial support dried up, the founders were forced to turn the school over to the state of New York. Under the State Board of Charities, children were subjected to prejudice, poor treatment, and long-term institutionalization, resulting in alienation from their families and cultures. In this harrowing yet essential book, Burich offers new and important insights into the role and nature of boarding schools and their destructive effect on generations of indigenous populations.

Table of Contents

1. “An Overwhelming Majority of the Indians Are Poor, Even Extremely Poor”

2. “Things Fall Apart”

3. Conceived in Hope, Born of Despair

4. “Crippled, Defective, and Indian Children”

5. “Up to This Day, I Ain’t Nothing”

6. “No Place to Go”

7. “Everyone Has Forgotten Me Though I’m Gonna Die”

Notes

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Keith R. Burich is professor of history at Canisius College in Buffalo, New York.

Related Interest

April 2016