Sketching the Adirondacks: Letters from the Wilderness, a new work of literary nonfiction from author Edward Pitts, tells the story of artists Jervis McEntee and Joseph Tubby as the pair journey through the Adirondacks in 1851, sketching what they find to use as painting reference. The book takes the form of a series of letters the pair write home, giving a personal dimension to their artistic journey. In time with the book’s release, we sat down to talk with the author about his process, how he views the characters, and his relationship to the wild places Tubby and McEntee sketched.

How did you first encounter Jervis McEntee and Joseph Tubby and why tell their story?

I first encountered McEntee and Tubby while doing research for my previous book, Beaver River Country. I had never heard of them or their sketching trip even though I was fairly familiar with nineteenth century Adirondack history. The fact that two young artists would spend the whole summer of 1851 sketching in the wild central Adirondacks seemed incredible. I couldn’t understand why very little had ever been written about their trip.

At a time when virtually all the visitors to the Adirondacks came for hunting, fishing or resource extraction, McEntee and Tubby traveled there solely to capture the beauty of the wilderness. McEntee’s written descriptions of the wilderness in his journal are quite evocative and poetic. I knew the story of the trip needed to be told, the question that I wrestled with as I did more research was how to best tell that story.

What research was required for the book? Did you have any difficulties finding reliable information?

There is actually a fair amount of information available about both artists and the trip, but finding it was a bit of an adventure. The primary source of reliable information is McEntee’s daily trip journal. A hand-written copy of that journal and a typed transcript are in the collection of the Adirondack Experience, the Museum on Blue Mountain Lake. Finding the trip journal was the easy part. A fellow historian told me about its existence during a casual conversation and when I expressed interest even sent me a digital copy.

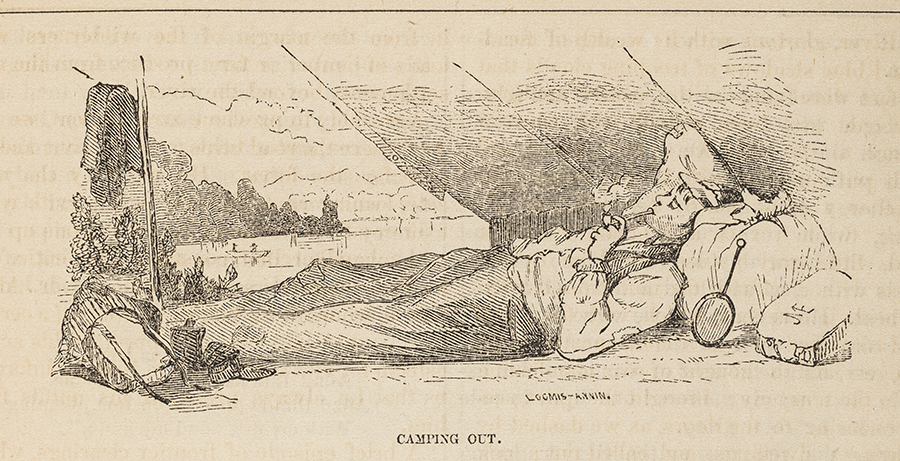

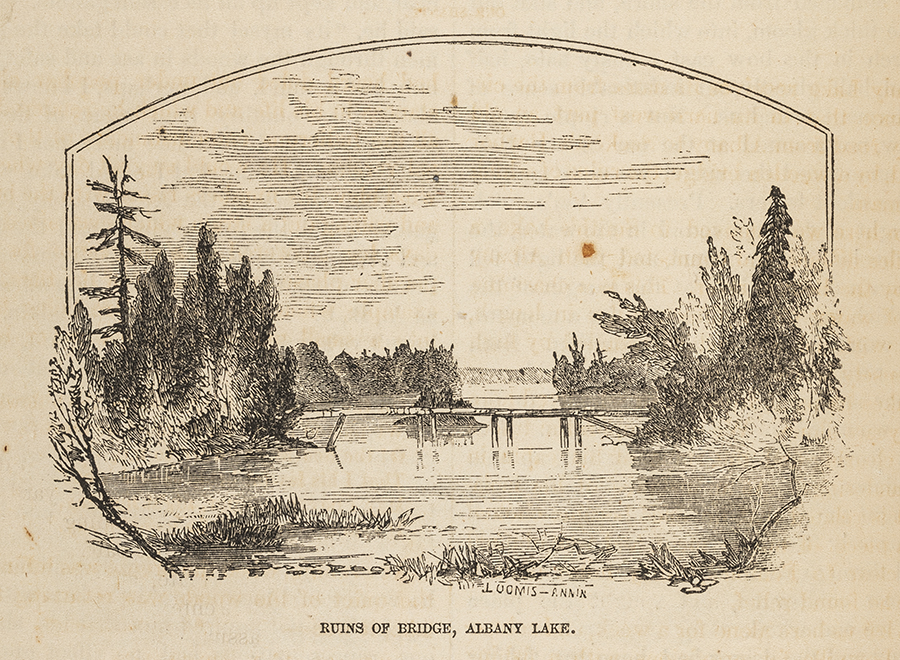

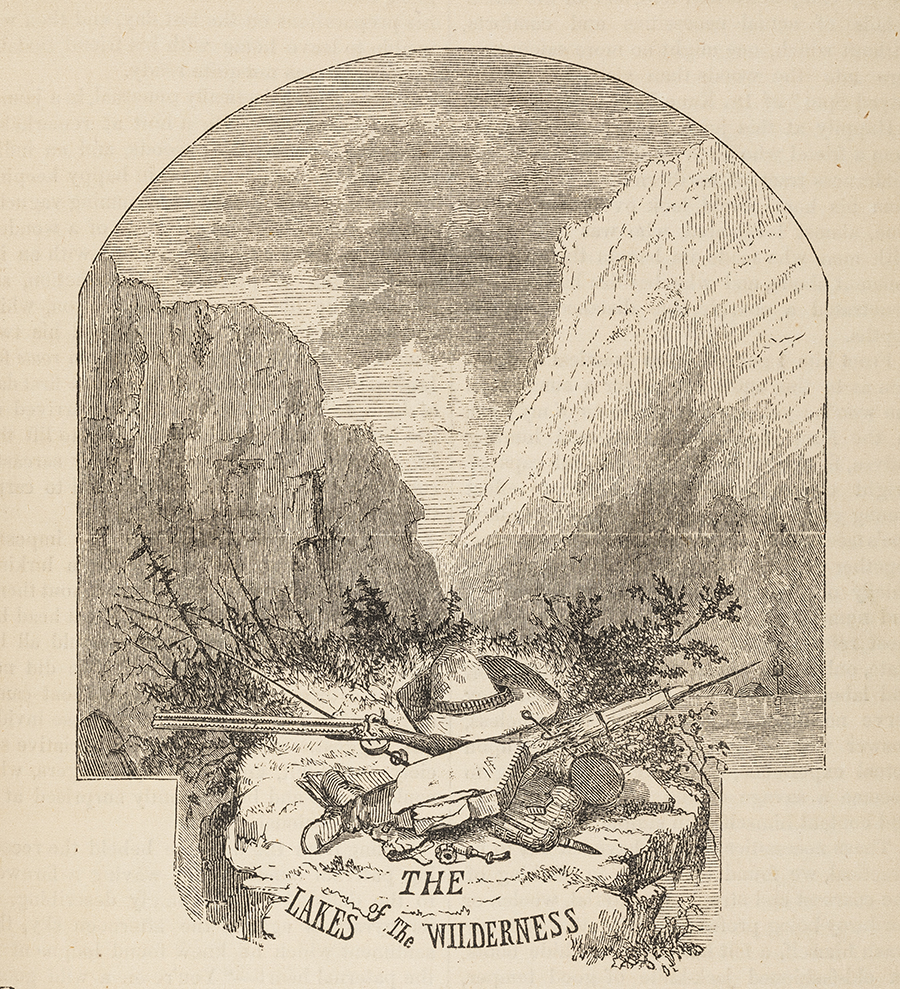

Eight years after the trip, in 1859, a lightly fictionalized account of the trip titled “The Lakes of the Wilderness” appeared in The Great Republic Monthly, an obscure magazine. For reasons known only to him, McEntee chose not to identify himself as the author. The article includes eighteen wonderful wood engravings of scenes from the trip. Hidden in the details of these illustrations it is possible, but not easy, to find McEntee’s monogram.

About one hundred years after that article appeared, a research associate at the Adirondack Museum [now renamed the Adirondack Experience], Dr. Warder H. Cadbury, found a reference to the article while researching an unrelated question. He was puzzled because he was extremely familiar with nineteenth century Adirondack writing, but he had never heard of the article. It took Cadbury several years and a few lucky guesses to discover that McEntee was the author. Cadbury’s discovery is fully documented in the research archive of the Adirondack Experience.

When I read “The Lakes of the Wilderness” I found it contained some important differences from the account in McEntee’s journal. The general story is the same, but there are significant additions as well as some interesting omissions. This led me to search the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution. It has collections of papers from McEntee and Tubby. I plowed slowly through both collections, but found very little directly about the trip, except for one wonderful long letter written by Tubby describing the events of July 3, 1851. A transcript of that letter is in my book.

My next line of research was to try to find the two descriptive articles McEntee’s journal says he had published in newspapers. I searched the online collections of historic newspapers, but found nothing. I eventually was able to track down both articles by following scattered references in secondary sources. Finding the original articles was complicated by the fact that they appeared in two different, long-defunct, local papers. The search was made even more difficult since neither article identified McEntee as the author, but were only signed with his initials. It’s the kind of fun only the most dedicated historian enjoys.

How did you settle on the letter writing form for “Sketching the Adirondacks?”

Once I had identified and collected all the necessary information about the sketching trip, I created a detailed outline, and began to arrange all the research material chronologically. I initially tried to tell the story by creating an abridged version of McEntee’s trip journal with a lot of contextual footnotes added, but the result proved to be essentially unreadable.

My ultimate decision was to tell the story of the sketching trip through the letters I imagined the artists might have written. This idea was suggested by entries in McEntee’s trip journal. During the trip, whenever they had the time, McEntee and Tubby wrote letters to their families and friends. McEntee’s journal records that he wrote dozens of such letters. The journal entries don’t include much of the context necessary to understand the importance of the events described. Letters would necessarily have had to include enough context for the recipients to follow the story.

Therefore, I selected key passages from McEntee’s writings, and constructed a series of letters around them. To each letter I added a descriptive note to fill out the context and indicate the sources of the information. The letters do not deviate from the historical record. They simply translate the record into a readable story using the techniques of literary nonfiction.

One of the really striking things about the book is how out of their depths the artists are as outdoorsmen, particularly at the beginning of their journey. Can you tell me about how you constructed character arcs for the two artists and how you view the two of them?

It’s true that the artists didn’t know much about wilderness camping before the trip. McEntee actually complained that there was little practical information about how to visit the Adirondacks available. Even so, they were confident that they had enough physical strength to attempt it. From time to time, McEntee brags in his journal about how well they managed hard tasks, even though their friends at home had openly doubted they would survive long in the wilderness.

I used this combination of caution and cockiness as the basis for the arc of their story. At the outset they both were a bit uncertain about their abilities as campers and as artists. At the same time, they were clearly enjoying the challenge. Whenever they got into difficulties, and that happened pretty frequently, they used their wits and and ever-present good spirits to somehow muscle through. As the trip progressed, they got into less trouble, and managed far better. This was true of their art as well. As their camping skills improved, thanks in large part to the efforts of Puffer their guide, they were able to focus more on making the sketches that were the very reason for the trip.

I got to know the artists fairly well while writing their story. I see Tubby as a hard-working, matter-of-fact man with a sensitive soul, who could make light of the most difficult situations. The bond of friendship he formed with McEntee during the trip proved to be lifelong. McEntee was a true romantic. His writing is always poetic and reflective. He was the prime mover of the trip; the one who set the itinerary and selected the scenes to sketch. Always the optimist, McEntee did not dwell on difficulties, but also liked to brag a bit about how well he overcame them. I like the young McEntee very much. I hope any future biographers will pay more attention to this part of his life.

Have you been able to visit any parts of the area McEntee and Tubby sketched?

I’ve visited almost all of the locations with only a few exceptions. Unfortunately, I’ve never been to the Indian Pass in the High Peaks. I can’t get to the Shingle Shanty Brook and Brandreth Lake because they are on private property. I revisited most of the other locations while writing the book to refresh my memory of the landscape. A photo of the place the artists camped at Lake Lila serves as the wallpaper on my home computer.

What are some of your favorite sketches from the journey?

My all-time favorite is McEntee’s pencil sketch of Wood’s cabin that appears on the cover of the book. The title image for “Lakes of the Wilderness” is also pretty great because it incorporates so many items that were key to the trip. The same can be said for the Genius loci that is reproduced near the end of my book. I also like McEntee’s self-portrait that appears in Letter #8. It’s the only image that I know of that shows him before he grew the beard he sported for the rest of his life.

Order a copy of Sketching the Adirondacks here.